Prepare for the unanticipated: Placenta accreta spectrum

Placenta accreta spectrum presents a complex obstetric challenge, characterized by the abnormal adherence of the placenta to the uterine wall, often leading to potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) refers to the pathologic adherence of the placenta where separation of the placenta from the uterus is not possible or results in potentially catastrophic hemorrhage. PAS is the result of disruption of the physiologic layers of the uterus normally present in pregnancy with—at minimum—loss of the transformed endometrium (decidua), and with more advanced disease, trophoblastic migration into the myometrium, serosa, and beyond.

Pathophysiology

The key issue with PAS is the lack of a cleavage plane between the placental basal plate and the uterine wall. Nomenclature has evolved with the understanding of disease pathology. Initially, PAS was thought to be a primary defect of trophoblastic biology that led to excessive invasion into the uterine layers.1 This resulted in terminology that included morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) and abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). More recently, there has been recognition that PAS is likely the result of a secondary defect of the endometrium-myometrial interface around the uterine scar or other anatomic defect that results in failure of normal decidualization and loss of subdecidual myometrium.1 This failure allows abnormal extravillous trophoblast attachment and excess fibrinoid deposition. Together they act as an adherent to the uterine wall.

Myometrial healing is also not completely regenerative, and the resulting fibrinous tissue is weaker, less elastic, and more prone to injury. As such, in many cases where there is a uterine scar, there is a degree of dehiscence of the scar, particularly as the lower uterine segment elongates in the third trimester, that also plays into PAS pathology.2 PAS severity clinically results from the interplay among the scar defect, proximity of placenta tissue to this defect, and lost myometrial thickness.1 Due to altered placental structure in PAS-affected regions, the uteroplacental circulation is altered, resulting in high-velocity maternal blood flow entering the intervillous spaces, termed lacunae.

Patient counseling

The concern for PAS has grown among obstetric providers due to its increasing frequency paralleling the concomitant rise of cesarean delivery. Since the 1980s, the rate of PAS has increased from 1 in 1250 births to as high as 1 in 272 births.3,4 All obstetrical providers should know how to counsel a patient with an identified concern for PAS. A discussion should include the increased risks of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, including preterm birth, prolonged operative times, transfusion, massive transfusion, genitourinary injury, intensive-care unit admission, secondary surgical procedures, and increased length of stay.5 PAS is now the leading cause of peripartum hysterectomy.6 As experienced multidisciplinary care leads to optimized maternal and fetal outcomes, patients with concern for PAS should be counseled on the need for a higher level of care and appropriate referrals should be placed.7,8 Longer-term concerns include loss of fertility with the potential for bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic organ prolapse. In addition, there is increasing recognition of the psychological toll of PAS on both the pregnant patient and the family unit, particularly in the event of relocation and/or prolonged hospitalization, with increased risks of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder.9

Screening and diagnosis

Screening for PAS begins with an assessment of risk factors based on patient history. The presence of placenta previa, particularly in the setting of prior history of cesarean delivery, is the best-established risk factor for PAS. Patients with a placenta previa without a prior cesarean delivery have a 3% risk of PAS, and the risk increases exponentially with each successive cesarean delivery (11% for 1, 40% for 2, 61% for 3, and 67% for 4 prior cesarean deliveries).10 Additional risk factors for PAS include in vitro fertilization, prior uterine procedures, multifetal gestation, and advanced maternal age.11

Patients with a known placenta previa and prior history of cesarean delivery should undergo sonographic assessment for the evaluation of PAS. If placental location cannot be safely determined transabdominally, transvaginal imaging should be pursued. Obstetric providers who are not able to evaluate for PAS should refer the patient to providers capable of making this assessment.

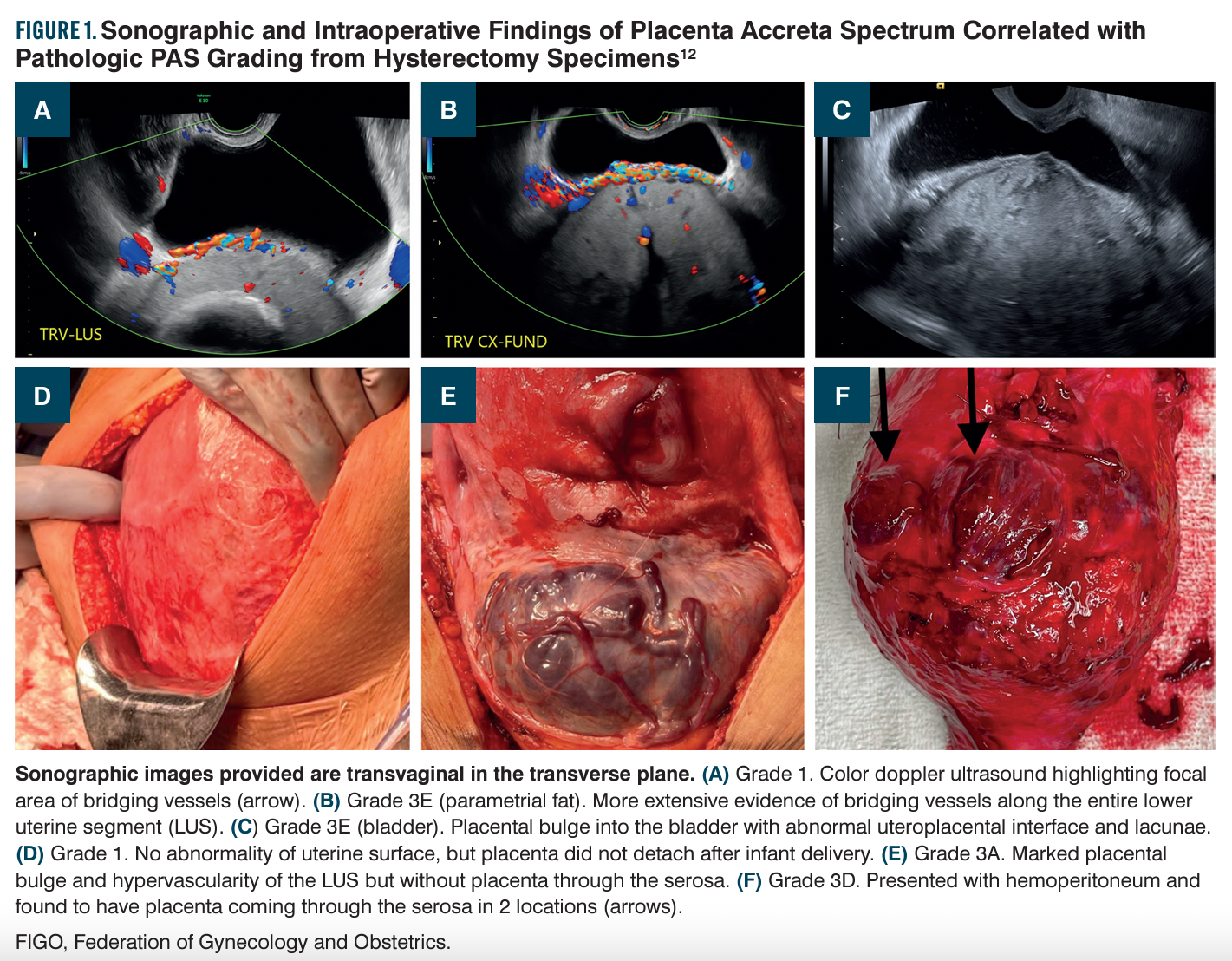

Ultrasound markers for PAS include placental lacunae, abnormalities of the uteroplacental interface, uterine/placental bulge, bridging vessels, and an exophytic mass (Figure 1).12 Placental lacunae result from distortion of placental cotyledons from high-velocity maternal blood flow. Abnormalities of the uteroplacental interface include both the loss of the hypoechoic zone (decidua basalis) between the myometrium and basal plate (retroplacental clear space) and thinning of the myometrium on sagittal imaging.12,13 The application of color Doppler imaging may be useful to assess bridging vessels and determine the extent of vascular involvement along the lower uterine segment.14-16

Ultrasound has a combined sensitivity based on established markers of 81.1% and specificity of 98.9%.12 Real-world use may be lower because reported estimates are based on mostly single centers with relatively high volumes of PAS cases. Use of a standardized approach for prenatal diagnosis with tools such as the placenta accreta index may increase the sensitivity of ultrasound.17

Though ultrasound markers are more commonly evaluated in the second and third trimesters, many can also be observed in the first trimester. Two additional first-trimester markers raise concern for the development of PAS: cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) and low implantation of the placenta. CSEP should be suspected when there is an empty uterine cavity and endocervix and the placenta, gestational sac, or both are implanted in the area of the prior hysterotomy scar.18 CSEP likely represents a continuum of PAS, and women who continue pregnancy should be referred to a center with expertise in PAS. Low implantation of the placenta has been defined variably as an inferior trophoblastic border of the gestational sac less than 5 cm from the external os in the first trimester, a gestational sac close to the internal os (up to 8 6/7 weeks of gestation), and/or placental implantation posterior to the maternal bladder (up to 13 6/7 weeks of gestation).12,19

The use of MRI for diagnosis of PAS remains less defined. It requires specialized expertise in placental MRI, and concerns remain about interreader variability.20 Reported overall sensitivity and specificity are high (94.4% and 84.0% respectively) but prone to selection bias because studies often are only obtained in indeterminate or very high-risk patients.21 Adjunctive use has been suggested for determination of lateral or posterior involvement and depth of invasion. Seven MR imaging markers have been defined: intraplacental dark T2 bands, uterine/placental bulge, low of the T2 retroplacental line, myometrial thinning or disruption, bladder wall interruption, focal exophytic placental mass, and abnormal vasculature of the placental bed.22

Classification and risk assessment

Prenatal diagnosis of PAS is based on suspicion from obtained imaging. Further classification is then determined based on clinical intraoperative findings and pathology. Traditional classifications were based on the layer of the uterus impacted and defined as accreta (loss of intervening decidua), increta (trophoblasts into the myometrium), and percreta (trophoblastic invasion through the serosa with possible extension to surrounding structures).23 Recently there has been recognition that more universal language is necessary for clinical and pathologic diagnosis of PAS that allows for better disease correlation and enhanced external validity. In 2019, an expert consensus panel on behalf of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) released guidelines for clinical diagnosis of PAS with a descriptive grading system.24 Accreta is now grade 1 and consistent with no separation of the placenta or placenta separation resulting in hemorrhage at the implantation site requiring further intervention. Increta is now grade 2 and consistent with the presence of uterine/placental bulge and hypervascularity. Percreta is now grade 3 with subdivisions based on where placental tissue is seen: through the serosa (3A), into the bladder (3B), or with extension into other pelvic organs (3C). In 2020, another expert panel released classifications and reporting guidelines for pathologic diagnosis that parallel the FIGO guidelines.25 Reassuringly this pathologic grading system has been found to correlate with clinical outcomes.26

Management

Patients with PAS identified prior to delivery should be delivered at a center with a level of maternal care III or IV designation (or equivalent) with a comprehensive and experienced multidisciplinary team to improve outcomes.21 This includes partners in obstetrics, maternal-fetal medicine, radiology (diagnostic and interventional), pelvic surgery (gynecologic oncology, urology, general surgery), anesthesiology, transfusion medicine, neonatology, family support, and experienced operative room and nursing personnel. Such care results in a lower likelihood of emergent delivery, lower blood loss, less transfusion, and for the neonate, higher Apgar scores and less respiratory distress.7,8 Delivery is typically performed at 34 0/7 to 35 6/7 weeks based on expert recommendation, but it can vary depending on patient history, prior episodes of bleeding, and staffing availability.21 In the United States, PAS confirmed intraoperatively is managed with hysterectomy with rare exceptions.

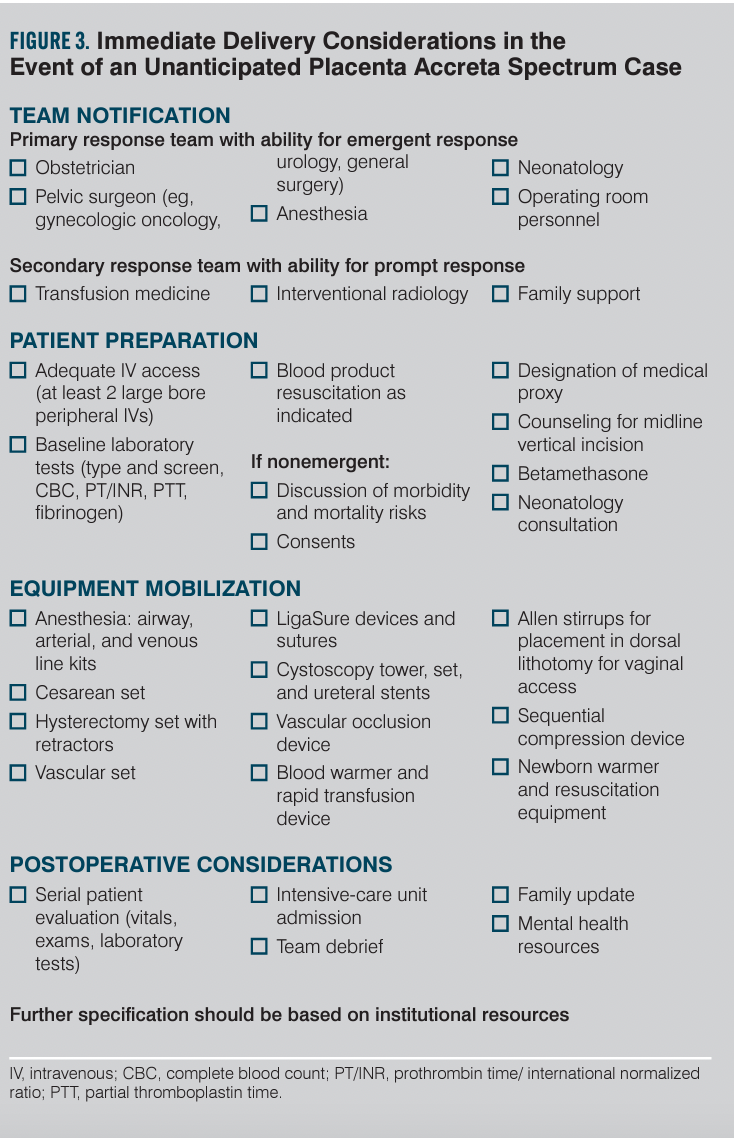

Antepartum patients who are candidates for corticosteroids should receive them prior to preterm delivery.27 Anemia diagnosed preoperatively should be optimized by intravenous (IV) iron therapy or transfusion. Baseline laboratory studies upon admission for delivery should include a type and cross match and coagulation profile. Sufficient IV access should be obtained with at minimum 2 large-bore IV lines or more invasive lines as determined in discussion with anesthesia. A protocol should be in place for blood products in the operating room as well as a massive transfusion protocol. One study’s results suggest that a minimum of 6 units of packed red blood cells be available for these cases, though the optimal amount is unknown.28 Cell salvage and rapid infusion equipment should be utilized if available. Operating room personnel should verify periodically that equipment is readily available in the event of an unanticipated PAS case.

Many components of the surgical management of PAS require further research. The optimal anesthesia for PAS is unclear. Options include general, neuraxial, or a combined approach. Neuraxial anesthesia with planned conversion to general anesthesia has the benefit of reduced fetal exposure, maternal bonding with the neonate, and a secured airway for resuscitation, but is less likely to be favored in emergency scenarios.29,30 Some centers use ureteral stents31 or balloon occlusion of the aorta32-34 as part of their management protocols, but it’s not yet determined which patients require these approaches.

Preparedness

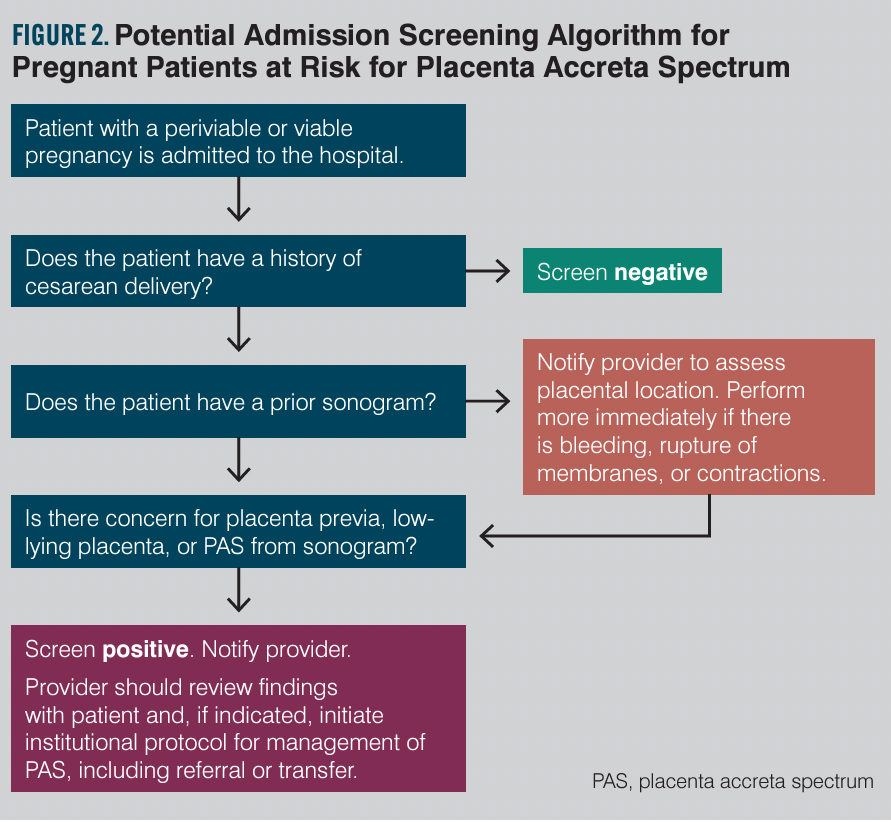

Texas House Bill 1164, which took effect in September 2021, requires that only centers with maternal level of care IV designation (or level III centers meeting all level IV center requirements for PAS) provide care for suspected PAS patients.35 This includes a multidisciplinary team with expertise for screening, evaluation, diagnosis, consultation, and management of PAS, including surgical and postpartum care. All hospital levels must have written guidelines and protocols in place for unanticipated PAS cases. Internal staff education and quality assurance/performance improvement are also required. Education is suggested via both formal lecture and simulation. Fostering telemedicine for referral and transfer as well as external outreach is required of centers that care for PAS patients. Given the increasing contribution of PAS to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, it is likely that in the future additional states will follow suit with similar requirements. To be proactive, hospitals and their providers should develop an admission screening process to flag women at risk for PAS. They also should develop checklists and protocols in the case of unanticipated PAS to enable system readiness. Suggested outlines for admission screening and immediate delivery considerations of unanticipated PAS are provided in Figures 2 and 3. The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recently released a special statement that included an emergency checklist, planning worksheet, and system preparedness bundle for PAS.36 These provide extensive guidance on pre-, intra-, and postoperative considerations and interdisciplinary team optimization. Additional resources can be found via the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists District XI’s webinar on PAS.37

Because optimal outcomes are seen at higher volume, multidisciplinary PAS centers,7,8 lower levels of care should also develop algorithms for transfer of care. Patients with concern for PAS identified prenatally should be transferred when the concern is identified; earlier referral facilitates optimal preoperative multidisciplinary evaluation and surgical planning. In the event of unanticipated PAS at the time of delivery, if the patient is clinically stable, consideration should be given for closure of the abdomen with patient transfer to a facility with PAS expertise if feasible. Protocols should be in place for activating a PAS management team, mobilizing equipment to control bleeding and perform hysterectomy, and providing blood products.11,36 Paramount is the ability of obstetrical providers to identify concern for PAS via pattern recognition findings, such as placental bulges and hypervascularity (Figure 1).

Conclusion

PAS is an increasing concern for obstetrical providers. To reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, a streamlined process for PAS must be developed. This includes clear pathways for sonographic assessment of risk, timely referral with prenatal suspicion, and development of appropriate teams and strategies for the management of PAS.

References

- Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D, Hussein AM, Burton GJ. New insights into the etiopathology of placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(3):384-391. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.038

- Einerson BD, Comstock J, Silver RM, Branch DW, Woodward PJ, Kennedy A. Placenta accreta spectrum disorder: uterine dehiscence, not placental invasion. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(5):1104-1111. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000003793

- Mogos MF, Salemi JL, Ashley M, Whiteman VE, Salihu HM. Recent trends in placenta accreta in the United States and its impact on maternal-fetal morbidity and healthcare-associated costs, 1998-2011. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(7):1077-1082. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1034103

- Read JA, Cotton DB, Miller FC. Placenta accreta: changing clinical aspects and outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;56(1):31-34.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Spong CY, Casey BM. Hemorrhagic placental disorders. In: Williams Obstetrics, 26th edition. McGraw Hill; 2022.

- Fleming ET, Yule CS, Lafferty AK, Happe SK, McIntire DD, Spong CY. Changing patterns of peripartum hysterectomy over time. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(5):799-801. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004572

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Outcomes of planned compared with urgent deliveries using a multidisciplinary team approach for morbidly adherent placenta. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):234-241. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002442

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):218.e1-218.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.08.019

- Ayalde J, Epee-Bekima M, Jansen B. A review of placenta accreta spectrum and its outcomes for perinatal mental health. Australas Psychiatry. 2023;31(1):73-75. doi:10.1177/10398562221139130

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226-1232. doi:10.1097/01.Aog.0000219750.79480.84

- Einerson BD, Gilner JB, Zuckerwise LC. Placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142(1):31-50. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000005229

- Shainker SA, Coleman B, Timor-Tritsch IE, et al. Special report of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Placenta Accreta Spectrum Ultrasound Marker Task Force: consensus on definition of markers and approach to the ultrasound examination in pregnancies at risk for placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(1):B2-B14. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.001

- Rac MWF, Dashe JS, Wells CE, Moschos E, McIntire DD, Twickler DM. Ultrasound predictors of placental invasion: the placenta accreta index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):343e1-343e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.022

- Herrera CL, Kim MJ, Xi Y, Dashe JS, Spong CY, Twickler DM. The placenta accreta index: do more ultrasound variables add value? Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(2):100832. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100832

- Yule CS, Lewis MA, Do QN, et al. Transvaginal color mapping ultrasound in the first trimester predicts placenta accreta spectrum: a retrospective cohort study. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40(12):2735-2743. doi:10.1002/jum.15674

- Shih JC, Kang J, Tsai SJ, Lee JK, Liu KL, Huang KY. The “rail sign”: an ultrasound finding in placenta accreta spectrum indicating deep villous invasion and adverse outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(3):292.e1-292.e17. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.018

- Happe SK, Yule CS, Spong CY, et al. Predicting placenta accreta spectrum: validation of the placenta accreta index. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40(8):1523-1532. doi:10.1002/jum.15530

- Miller R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(3):B9-B20. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.024

- Moschos E, Wells CE, Twickler DM. Biometric sonographic findings of abnormally adherent trophoblastic implantations on cesarean delivery scars. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33(3):475-481. doi:10.7863/ultra.33.3.475

- Khan A, Do QN, Xi Y, et al. Inter-reader agreement of multi-variable MR evaluation of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) and association with cesarean hysterectomy. Placenta. 2022;126:196-201. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2022.07.005

- Cahill AG, Beigi R, Heine RP, Silver RM, Wax JR. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7: placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(6):B2-B16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.042

- Jha P, Pōder L, Bourgioti C, et al. Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) and European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) joint consensus statement for MR imaging of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(5):2604-2615. doi:10.1007/s00330-019-06617-7

- Silver RM, Branch DW. Placenta accreta spectrum. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1529-1536. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1709324

- Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Langhoff-Roos J, Fox KA, Collins S; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146(1):20-24. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12761

- Hecht JL, Baergen R, Ernst LM, et al. Classification and reporting guidelines for the pathology diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders: recommendations from an expert panel. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(12):2382-2396. doi:10.1038/s41379-020-0569-1

- Salmanian B, Shainker SA, Hecht JL, et al. The Society for Pediatric Pathology Task Force grading system for placenta accreta spectrum and its correlation with clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(5):720.e1-720.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.002

- Reddy UM, Deshmukh U, Dude A, Harper L, Osmundson SS. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #58: use of antenatal corticosteroids for individuals at risk for late preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(5):B36-B42. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.07.023

- Miller SE, Leonard SA, Meza PK, et al. Red blood cell transfusion in patients with placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(1):49-58. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004976

- Warrick CM, Markley JC, Farber MK, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum disorders: knowledge gaps in anesthesia care. Anesth Analg. 2022;135(1):191-197. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000005862

- Warrick CM, Rollins MD. Peripartum anesthesia considerations for placenta accreta. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(4):808-827. doi:10.1097/grf.0000000000000403

- Scaglione MA, Allshouse AA, Canfield DR, et al. Prophylactic ureteral stent placement and urinary injury during hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(5):806-811. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004957

- Clifford C, Kobernik E, Rolston A, Uppal S, Napolitano L, Carver A. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in cesarean hysterectomies for placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(suppl 1):S201-S202. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.346

- Ioffe YJM, Burruss S, Yao R, et al. When the balloon goes up, blood transfusion goes down: a pilot study of REBOA in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2021;6(1):e000750. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2021-000750

- Whittington JR, Pagan ME, Nevil BD, et al. Risk of vascular complications in prophylactic compared to emergent resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in the management of placenta accreta spectrum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-4. doi:10.1080/14767058.2020.1802717

- Relating to Patient Safety Practices Regarding Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorder. HB 1164, 87th sess (Texas 2021). June 15, 2021. https://legiscan.com/TX/text/HB1164/2021

- Einerson BD, Healy AJ, Lee A, et al; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Special Statement: emergency checklist, planning worksheet, and system preparedness bundle for placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;230(1):B2-B11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2023.09.001

- Placenta accreta spectrum disorder clinical and designation guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. December 2, 2022. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/placenta-accreta-spectrum-disorder-clinical-and-designation-guidelines

Newsletter

Get the latest clinical updates, case studies, and expert commentary in obstetric and gynecologic care. Sign up now to stay informed.

S4E1: New RNA platform can predict pregnancy complications

February 11th 2022In this episode of Pap Talk, Contemporary OB/GYN® sat down with Maneesh Jain, CEO of Mirvie, and Michal Elovitz, MD, chief medical advisor at Mirvie, a new RNA platform that is able to predict pregnancy complications by revealing the biology of each pregnancy. They discussed recently published data regarding the platform's ability to predict preeclampsia and preterm birth.

Listen