Rosacea: disagnosis and treatments for women, and best interventions for pregnant patients

A 35-year-old woman presents with a rash on her face, which worsened following a sunburn on a beach trip and persisted for more than 6 months. What's the diagnosis?

Figure

A 35-year-old woman presents with a rash on her face (Figure), which worsened following a sunburn on a beach trip and persisted for more than 6 months. More recently, she noticed small red bumps and prominent blood vessels on her face. Her face and eyes were dry and itchy, and her face was somewhat swollen. She was embarrassed about the rash and wore more makeup to try to conceal it.

What is her diagnosis, and how would you treat her?

Differential diagnosis

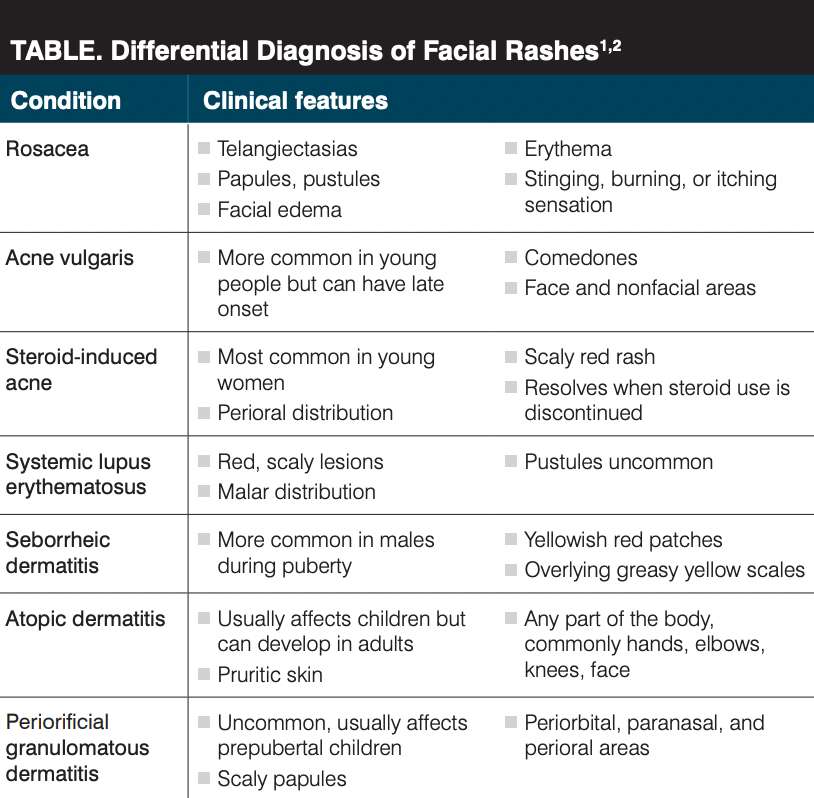

There is a broad differential for erythematous facial rashes. Key features of the patient’s rash include appearance after sun exposure, chronicity, papules, telangiectasias, dryness and pruritis, and swelling. Her rash is on the cheeks and nose and around the eyes. Possible diagnoses and their clinical features are listed in the Table.1,2

The patient’s presentation most matches that of rosacea.

Diagnosis: rosacea

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the face. Approximately 10% of individuals globally have rosacea. It is most common in women, individuals who are aged 35 to 50 years, and fair-skinned individuals.3 The primary features of rosacea include flushing, nontransient erythema, papules and pustules, and telangiectasias. Secondary features include burning or stinging sensations; plaques; dryness; edema; ocular manifestations such as burning or itching, inflammation, styes, and corneal damage; nonfacial lesions; and phymatous changes such as skin thickening. These features can be scored as absent, mild, moderate, or severe in a global assessment.3 There are 5 main clinical subtypes of rosacea: erythematotelangiectatic (ETR), papulopustular (PPR), phymatous, ocular, and other variants.3

Rosacea has a negative impact on quality of life and the social and psychological well-being of patients. In a qualitative study of women with rosacea, participants endorsed feelings of shame, low mood, anxiety, embarrassment, and self-blame, with the need to conceal and “battle” with their skin. This battle includes the financial costs of treatment as well as the social cost of hiding their challenges as a way to fit in and avoid rejection.4

Rosacea in women

Rosacea may be more common in women because of reproductive and hormonal factors. The onset of rosacea is more common in premenopausal women than postmenopausal women, and an increased risk of rosacea is associated with menopausal hormonal therapy, particularly longer duration of use and therapy containing oral conjugated estrogen.4 Rosacea risk is increased in nulliparous women (with decreased risk with increasing number of births) and women of advanced maternal age.5

Pregnancy is associated with hormonal changes and thus exacerbates rosacea. Rosacea fulminans (RF), a rare and severe subtype of rosacea, may develop during pregnancy and is associated with worse obstetric outcomes.6

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of rosacea is not well defined. There may be an abnormal immune activation or cutaneous vascular homeostasis. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) may induce damage in keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells through the release of IL-1 and TNF-α. UV-A exposure leads to decreased activity of matrix metalloproteins and inhibition of collagen synthesis, and UV-B exposure leads to the production of inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic factors.3 Rosacea may be triggered by microbes such as Demodex folliculorum and Helicobacter pylori and may be a manifestation of systemic diseases such as obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Additionally, other metabolic, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders— as well as some malignancies, drugs, and foods—may be associated with rosacea.3

Treatment

With varying pathogenesis and presentations, treatment should combine several modalities and be patient specific. All patients should receive education about rosacea and its triggers. All treatments should include high-SPF broad-spectrum sunscreen, soap-free cleansers, and moisturizers. Heavy or harsh products should be avoided.3

Topical therapies include azelaic acid, metronidazole, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, brimonidine tartrate, oxymetazoline hydrochloride, and ivermectin. Azelaic acid reduces erythema and inflammation by decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity, whereas metronidazole reduces ROS release from neutrophils. Sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur is anti-inflammatory and with metronidazole can decrease papules and overall disease severity, but it should not be used in patients with renal disease or known drug hypersensitivity. Brimonidine tartrate is an α-adrenergic receptor agonist that vasoconstricts subcutaneous vessels, improving flushing, erythema, and edema. Oxymetazoline hydrochloride is an α-1 agonist used for reducing erythema. Ivermectin is used to manage PPR rosacea. It has anti-parasitic and anti-inflammatory effects, upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines, inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines, and decreasing phagocytosis and chemotaxis.3

Second-line topical therapies include calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), benzoyl peroxide, and topical antibiotics (clindamycin, erythromycin). Calcineurin inhibitors prevent the dephosphorylation of the nuclear factors of T cells, blocking transcription of cytokines. They work best in ETR and PPR rosacea. Benzoyl peroxide and topical antibiotics may be more irritating and less effective.3

Oral therapies are mostly used for papulopustular rosacea and include tetracyclines, macrolides, metronidazole, and isotretinoin. Tetracyclines inhibit angiogenesis, chemotaxis, inflammatory cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases. Macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin) are useful in patients who cannot tolerate tetracycline therapy and are safe and effective. Isotretinoin is used to manage refractory ETR and PPR; it improves erythema and inflammation and can be used for longer periods of time than oral antibiotics, though contraception is important in women of child-bearing age. Metronidazole decreases inflammation in PPR.3

There are several types of laser therapies available for rosacea, such as intense pulsed light, pulsed dye laser, potassium titanyl phosphate, and long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser. Ablative lasers are used to manage phymatous rosacea. Light-based therapies are especially effective in managing the vascular manifestations of rosacea (flushing, erythema, telangiectasia). Patient satisfaction is often high with these methods, with good cosmetic results.3

Two other treatment options include surgery and botulinum toxin (BTX). Surgery can be used to excise rhinophyma, a nasal deformity seen in cases of severe rosacea. BTX has been used off label to decrease erythema and flushing. It inhibits the release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, and it blocks the release of acetylcholine from peripheral autonomic nerve endings of cutaneous vessels.3

Management in pregnancy

Rosacea management during pregnancy is challenging because there is a lack of randomized controlled trials to review and several treatments are contraindicated during pregnancy because of harmful fetal effects. RF is also difficult to manage with conventional rosacea treatments. Topical ivermectin, as a category C drug, should not be a first-line therapy in pregnant patients. Azelaic acid, brimonidine, and metronidazole may be OK to use. Regarding oral therapies, tetracyclines are associated with discoloration of teeth in the fetus, and isotretinoin is a teratogen. Azithromycin is a safe option. Light-based therapies also may be safe and effective during pregnancy. In case reports of RF in pregnancy, the most common treatment was oral corticosteroids.6

Patient case revisited

After explaining the diagnosis of rosacea, it was recommended that the patient use soap-free cleansers, moisturizers, and high-SPF broad-spectrum sunscreen every day. Azelaic acid 15% gel and oral doxycycline 40 mg daily were prescribed. If the patient were pregnant or becomes pregnant in the future, she could take azithromycin instead of doxycycline. The patient may also benefit from intense pulsed light for her vascular manifestations of rosacea.

Important points

- Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the face and mainly affects women and fair-skinned individuals.

- The pathophysiology of rosacea is not well-defined but may be related to inflammation and cellular damage; it is also associated with certain diseases and drugs.

- There are several treatment modalities available, including topical therapies, oral therapies, and laser/light therapies.

- Rosacea is affected by hormonal and reproductive factors. Special consideration must be made when treating pregnant patients with rosacea.

- Rosacea can be associated with feelings of shame, embarrassment, and anxiety, negatively affecting quality of life. Diagnosis should be prompt, and treatment should be sensitive to patient needs.

References

- Johnson SM, Berg A, Barr C. Recognizing rosacea: tips on differential diagnosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(9):888-894.

- Al-Qassabi AM, Al-Busaidi K, Al Baccouche K, Al Ismaili A. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in an adult: a case report with review of literature. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020;20(1):e100-e103. doi:10.18295/squmj.2020.20.01.015

- Sharma A, Kroumpouzos G, Kassir M, et al. Rosacea management: a comprehensive review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;21(5):1895-1904. doi:10.1111/jocd.14816

- Carter C, Martin K, Gordon C, Goulding JMR. Exploring the lived experience of women with rosacea: visible difference and psychological impact. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(2):366-367. doi:10.1111/bjd.20768

- Wu WH, Geng H, Cho E, et al. Reproductive and hormonal factors and risk of incident rosacea among US White women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(1):138-140. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.865

- Gomolin T, Cline A, Pereira F. Treatment of rosacea during pregnancy. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(7). doi:10.5070/D327754360

Newsletter

Get the latest clinical updates, case studies, and expert commentary in obstetric and gynecologic care. Sign up now to stay informed.

Solutions for spinal headaches

December 7th 2021Curbside Consults delivers expert perspectives from physicians outside the ob-gyn specialty to provide insight into various health issues affecting pregnant women. In this installment, we learn more about the diagnosis and management of headaches in postpartum patients.

Read More

Curbside Consults delivers expert perspectives from physicians outside of the ob/gyn specialty to provide insight into various health issues affecting pregnant women, about which they are experts. This new section is the brainchild of Editorial Advisory Board member Christine Isaacs, MD.

Read More