Urodynamic studies (UDS) for bladder testing are common practice in the workup of patients with urinary symptoms and pelvic organ prolapse, particularly those with neurogenic disorders, complex symptoms requiring diagnostic evaluation to clarify a cause of incontinence, and for those considering invasive and surgical treatment options.

Takeaways

- Urodynamic bladder testing is used to assess patients with urinary symptoms, pelvic organ prolapse, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction, or inconclusive causes of incontinence, and patients planning to undergo invasive and surgical treatment.

- The use of 2% intraurethral lidocaine does not have any statistically or clinically significant effect on urodynamic filling or voiding parameters.

- Urodynamic bladder testing is not a substantially uncomfortable procedure for most patients.

- The use of 2% intraurethral lidocaine may relieve some discomfort during urodynamic bladder testing.

- Consider 2% lidocaine jelly for urodynamic studies in patients who are anxious about catheter insertion or those with a history of substantial pain with urethral instrumentation.

UDS testing typically is a composite of several procedural steps:

- uroflowmetry to determine maximal flow rate, voiding pattern, and postvoid residual;

- a cystometrogram (cystometry) to determine a patient’s sensation during filling, presence or absence of detrusor overactivity, bladder compliance, and measurement of leak point pressures with Valsalva maneuver and cough;

- a pressure flow study to further assess bladder emptying;

- possibly a urethral pressure profile to measure maximum urethral closure pressure.

Due to its invasive nature involving the use of thin pressure-detecting plastic catheters in the urethra/bladder and the vagina or rectum, patients often experience anxiety about this testing. In clinical practice, patients will sometimes ask whether a numbing agent—such as topical lidocaine jelly—could be used for the urethral catheter insertion to help alleviate the discomfort of urodynamic catheter placement, which often causes a temporary stinging or burning sensation. It is uncertain if using topical urethral lidocaine jelly for catheter insertion might distort UDS results, particularly regarding the more subjective assessments during cystometry such as sensation during filling and bladder capacity. There are also concerns that objective bladder emptying measurements during the pressure flow study could be affected if numbing of the urethra blunts sensory nerves that amplify bladder contractions that maintain efficient emptying.1,2 Finally, it has also been hypothesized that lidocaine jelly may impair/mask detrusor overactivity (DO), or bladder spasms, during UDS, which is relevant in the assessment of patients reporting urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urgency incontinence.

Investigations of the use of intraurethral lidocaine jelly

Research into the use of intraurethral lidocaine jelly and its effects—if any—on cystometric and voiding parameters during UDS testing has yielded inconsistent findings, and there is a paucity of research on its impact on patient discomfort during UDS testing. Due to its effect as a sodium channel blocker and ability to provide an analgesic numbing effect,3 it is logical to presume that intraurethral lidocaine jelly may provide some relief of discomfort for patients during catheterization. In a small study by Kisby et al,4 23 healthy female volunteers underwent UDS bladder testing after being randomly assigned to intraurethral placebo water-based lubricant or 2% lidocaine jelly. The trial reported that the 2% intraurethral lidocaine jelly did not have any meaningful impact on most voiding metrics but did show greater interrupted flow patterns and more electromyography (EMG) activity. The study also reported no significant differences in pain perception between either group.4

Similarly, a recent larger trial by Avondstondt et al5 that randomly assigned 134 participants undergoing complex UDS to 2% lidocaine jelly or water-based lubricant identified no significant differences in a visual analog scale (VAS) of pain but also found no differences in either filling or voiding metrics.5 However, the primary outcome was pain at 4 to 6 hours post procedure, and by this point discomfort was scored as very low in both groups, making it difficult to identify a clinically important improvement.5 This study, like the one by Kisby et al4, did not attempt to utilize patients as their own control.

Other previous larger studies have reported less pain with the use of lidocaine jelly for a cotton-tipped swab test of the urethra, during urethral catheterization, and for the placement of urodynamic catheters.6,7 However, these trials also did not utilize the patient as their own control or assess how cystometric and voiding parameters might have been affected by the addition of lidocaine jelly.6,7

In a study of 21 patients, both men and women, that utilized the patient as their own control, urodynamics testing was performed on participants with urgency and urge incontinence but no DO on initial (ie, water-based lubricant) cystometry. Then repeat cystometry was performed with lidocaine jelly as the lubricant. Curiously, several of the participants then did demonstrate DO. The investigators suggested that it is possible lidocaine jelly may “increase the precision of urodynamics in patients with suspected overactive bladder” by increasing the observation of DO.8

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Oktaviani et al9 reviewed 3 randomized control trials examining urodynamic parameters after lidocaine compared with water-based lubricants. They concluded that all urodynamic parameters were similar after lidocaine compared with the water-based lubricant, but that pain intensity was no different. This systematic review was limited by the inclusion of very few trials and did not include Avondstondt et al.5

Finally, a recent double-blind randomized control trial by Hicks et al10 aimed to investigate if the use of a topical 2% lidocaine jelly injected into the urethra for complex cystometry and pressure flow study would have any impact on cystometric filling metrics or bladder emptying. This trial also assessed patient discomfort at different times throughout bladder testing: during urethral catheter insertion, at various points during filling, and during the pressure flow study (ie, when the patient was actively voiding after reaching maximum capacity). It also assessed patients’ overall impression of discomfort throughout the procedure. The urodynamicist was also asked to assess their perception of patient discomfort overall for the procedure. Discomfort was measured utilizing a 100-mm VAS.10 A change or decrease in 10 to 11 mm out of a 100-mm VAS pain score was considered clinically significant based on previous reports.11,12 Importantly, this trial was conducted utilizing the patient as their own control. UDS testing was conducted as normally would be done (UDS 1) with a water-based lubricant. Patients then were randomly assigned to receive either additional water-based lubricant or topical 2% lidocaine. The urodynamicist and patient were both blinded to the randomization. A clinical research coordinator conducted the randomization, drew up 5 cc of either the water-based lubricant or 2% lidocaine jelly, and gave the syringe to the urodynamicist for injection. After 5 minutes to allow the lidocaine jelly, if present, to reach its full effect, UDS 2 was performed with complex cystometry and pressure flow study in the same manner as UDS 1. Cystometric parameters and pressure flow study readings were recorded for both UDS 1 and UDS 2, and patient and provider perceptions of patient discomfort were captured for all time points.10

In the trial, 361 individuals were assessed for eligibility. Of those, 63 consented, were randomly assigned, and completed the trial. Included were women 18 years and older already planning UDS testing for evaluation of urinary incontinence or in anticipation of pelvic organ prolapse repair surgery. Exclusion criteria included any neurologic disease that might have an impact on voiding or ability to maintain continence (eg, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, stroke); any active urinary tract infection; prolapse that could not be adequately reduced for the procedure; interstitial cystitis, bladder pain syndrome, or painful bladder syndrome; pregnancy; breastfeeding; and/or allergy or hypersensitivity to lidocaine or other local anesthetics.10

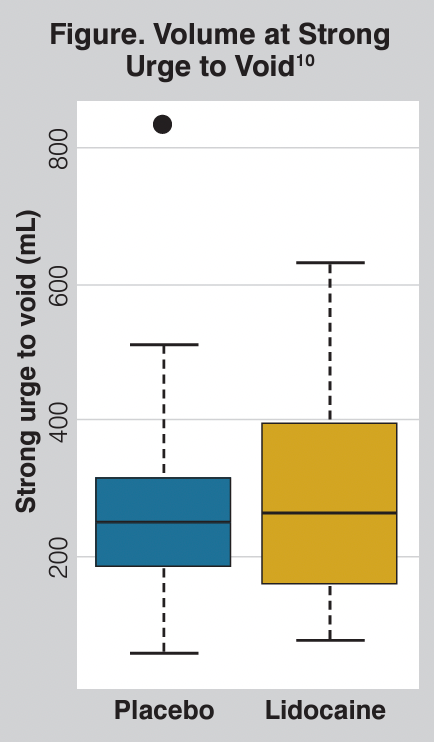

The study hypothesis was that 2% intraurethral lidocaine jelly would not meaningfully impact bladder sensation during cystometry filling. The primary outcome was the bladder volume at the point of strong desire to void (UDS 1 vs UDS 2), explained to the patient as, “When you feel like if you were driving in the car, and you would need to find a place to pull over.” The study was designed as an equivalence trial because it was assumed there would be no difference in the mean value of the 2 groups. Since it is unclear from current literature whether DO would impact findings, patient randomization was stratified based on the presence or absence of DO during UDS 1. Secondary objectives included other filling and voiding metrics: volumes during filling at first sensation (when patients first felt the sterile water in the bladder), first urge to void (described as, “When you feel like you might have to [urinate] in 20 to 30 minutes, but not right away”), and maximum bladder capacity (“When you feel like you’re full and can’t hold anymore”); bladder compliance (ie, the bladder maintaining a steady internal pressure while progressively filling to larger volumes); and, during voiding, the maximum flow rate, voiding patterns, voided volume, postvoid residual volume, voiding efficiency, detrusor pressure at peak flow and at maximum pressure, and EMG activity.10

For the primary outcome, volumes at strong urge were indeed approximately equivalent when comparing UDS 1 with UDS 2 (ie, after randomization to the lidocaine or water-based lubricant) (Figure).10 There were no significant differences in other filling metrics. Adherence was normal in all participants. Similarly, there were no differences in voiding metrics. Concerning participant discomfort, the raw scores for pain were typically quite low: median 10 mm on a scale of 0 to 100 mm, indicating that most participants did not find the procedure too uncomfortable. However, when comparing the change in discomfort in UDS 1 with UDS 2, there were statistically significantly greater improvements in discomfort after lidocaine instillation for the pressure flow study and for the participants’ overall perception of discomfort during the procedure. Likewise, the blinded urodynamicist also perceived less discomfort in the participants having received lidocaine for UDS 2.10

This trial’s results summarized that for women participating in UDS testing for evaluation of urinary incontinence or lower urinary tract symptoms, similar to the Avondstondt trial,5 most participants did not report substantial discomfort with the testing in general. However, the use of intraurethral 2% lidocaine jelly may decrease the discomfort of UDS bladder testing (in particular for a subpopulation of women prone to experience greater discomfort) without impacting cystometric and voiding metrics in any clinically or statistically significant way.

Conclusion

Therefore, in women with anxiety regarding invasive UDS bladder testing or with a history of difficult or painful past urethral instrumentation, the use of intraurethral 2% lidocaine jelly may help decrease discomfort without affecting diagnostic test results and may be considered a reasonable alternative to standard water-based lubricant for urethral catheterization.10

References

- Bump RC. The urethrodetrusor facilitative reflex in women: results of urethral perfusion studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(4):794-804. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70328-0

- Jung SY, Fraser MO, Ozawa H, et al. Urethral afferent nerve activity affects the micturition reflex; implication for the relationship between stress incontinence and detrusor instability. J Urol. 1999;162(1):204-212. doi:10.1097/00005392-199907000-00069

- Beecham GB, Nessel TA, Goyal A. Lidocaine. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kisby CK, Gonzalez EJ, Visco AG, Amundsen CL, Grill WM. Randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of intraurethral lidocaine on urodynamic voiding parameters. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(4):265-270. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000544

- Avondstondt AM, Chiu S, Salamon C. Periurethral lidocaine does not decrease pain after urodynamic testing in women: a double-blinded randomized control trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(5):e528-e532. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000983

- Özel BZ, Sun V, Pahwa A, Nelken R, Dancz CE. Randomized controlled trial of 2% lidocaine gel versus water-based lubricant for multi-channel urodynamics. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(9):1297-1302. doi:10.1007/s00192-018-3576-8

- Chan MF, Tan HY, Lian X, et al. A randomized controlled study to compare the 2% lignocaine and aqueous lubricating gels for female urethral catheterization. Pain Pract. 2014;14(2):140-145. doi:10.1111/papr.12056

- Edlund C, Peeker R, Fall M. Lidocaine cystometry in the diagnosis of bladder overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20(2):147-155. doi:10.1002/1520-6777(2001)20:2<147::aid-nau17>3.0.co;2-g

- Oktaviani DP, Soebadi MA, Kloping YP, Hidayatullah F, Rahman ZA, Soetojo S. Intraurethral lidocaine use during urodynamics in female patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk J Urol. 2021;47(5):366-374. doi:10.5152/tud.2021.21182

- Hicks C, Schaffer JI, Pruszynski JE, Rahn DD. Impact of intraurethral lidocaine on cystometric parameters and patient discomfort: a randomized controlled trial. Urol Nurs. 2022:42(5):237-243,257. doi:10.7257/2168-4626.2022.42.5.237

- Kelly AM. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J. 2001;18(3):205-207. doi:10.1136/emj.18.3.205

- Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):424-429. doi:10.1093/bja/aew466