Management of acute postoperative pain is essential for appropriate and compassionate postoperative care. Uncontrolled or even suboptimal control of postoperative pain can have numerous undesired consequences including negative patient experience, prolonged length of stay, and postoperative complications.1 Although the likelihood is low, poorly controlled postoperative pain may also give way to chronic pain, furthering the negative impact. Given the potential deleterious effects and risk of chronic dependence, recent practice has moved away from opioid use in the management of postoperative pain. This has provided surgeons with a broad array of effective alternatives to choose from. In this article, we aim to review interventions available for acute pain management during the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care.

Takeaways

- Adequate management of acute postoperative pain is crucial for ensuring appropriate and compassionate care. Poorly controlled pain can lead to negative patient experiences, prolonged hospital stays, and even postoperative complications.

- Because of the potential risks associated with opioids, recent practice has moved towards alternative methods for managing postoperative pain. Surgeons now have a variety of effective non-opioid options to choose from, reducing the likelihood of chronic dependence.

- Preoperative counseling and education are essential components of enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Educating patients about their postoperative plan, including pain management strategies and expectations, can help reduce anxiety and improve engagement in their own care.

- Multimodal analgesia, combining non-opioid medications like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen, has shown to reduce reliance on opioids while still effectively controlling acute postoperative pain. NSAIDs and acetaminophen are recommended for around-the-clock administration for a few days post-surgery.

- Special considerations, such as patient allergies or contraindications, should be taken into account when planning pain management strategies. Tailoring the approach to each patient's needs and collaborating with them throughout the process is essential for optimizing postoperative pain control and overall experience.

Before the day of surgery

Successful management of postoperative pain requires that attention be paid at all perioperative patient touch points and typically includes use of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways. ERAS pathways are a compilation of evidence-based, multimodal care pathways that span the perioperative period. Adherence to such pathways improves surgical outcomes by maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing the postoperative stress response, including postoperative pain.

Proper counseling and education in the preoperative period is the first tenet of ERAS pathways and ensures patients have a clear understanding of their postoperative plan and recovery.1 Providing the patient with education and ample time to prepare for recovery plays an important role not only in setting appropriate expectations, but also in reducing patient anxiety and improving engagement in their own care.2-4 Expectations should be set for pain quality, level, duration, and progression. Setting expectations for postoperative pain and appropriate levels of function also helps to minimize opioid use in the short and long term.5 Preoperative education should include a brief review of typical prescription and over-the-counter medications that will aid in pain management and how these medications should be taken, whether around-the-clock or as needed. Introducing pain management strategies prior to surgery allows patients to be involved in management decisions proactively.

Preoperative counseling most often occurs verbally during a clinical encounter, and for many patients it will be the first time hearing this information. The average individual will remember only 3 to 5 main points when presented with new information, however. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to bring family members or other members of their postoperative care team to their preoperative appointments, not just on the morning of surgery. Additionally, supplementing office counseling with written material or videos gives the patient and their care team the opportunity to revisit the information at any point in the perioperative time frame.

Preoperative education and counseling are especially pertinent for patients with chronic pain, whether or not they are receiving medications. Setting expectations and coordinating with relevant specialists is paramount to successful postoperative pain management in this population.

On the day of surgery

Preoperative administration of nonopioid pharmacologic agents decreases postoperative pain by reducing the pain response, surgical stress, and inflammation.6 Early ERAS pathways included intravenous administration of acetaminophen. However, evidence has shown that oral acetaminophen provides substantial cost savings without compromise in efficacy when used in multimodal pain regimens.6-8 At the current time, ERAS pathways typically call for a combination of oral acetaminophen and celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor) to be administered to patients prior to going into the operating room.1

Preemptive treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is also integral in standard ERAS pathways. Although most antiemetics will not reduce pain, prophylaxis against PONV only stands to positively impact pain by preventing vomiting. Intravenous dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid, is well studied and shown to reduce PONV when administered preoperatively or intraoperatively.1 Similar to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids reduce prostaglandin production, which explains why findings from several studies demonstrate that preoperative or intraoperative use of dexamethasone is associated with reduced postoperative pain as well.9

Route of surgery plays an important role in predicting postoperative pain. When feasible, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is preferred as it will have a significant positive impact on the patients’ postoperative pain experience. Those undergoing MIS benefit from infiltration with local anesthetic at laparoscopic incision sites.1 It is commonly performed before skin incision, after skin closure, or both. Although infiltration after skin closure provides temporary analgesia at the skin incision, there is also theoretical benefit associated with infiltration prior to skin incision, as this sequence would block the initial transmission of noxious stimuli. The literature findings supporting this technique are variable as to whether it reduces postoperative pain or opioid requirements after surgery, but this intervention is low cost and poses minimal risk. There are no data to suggest superiority of one short-acting local anesthetic over another. Duration of a local anesthetic can be increased with the addition of epinephrine; however, data do not support improved outcomes, and epinephrine may not be appropriate for all patients.

The transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is a commonly used regional technique to provide postoperative analgesia and can be used as an alternative to port-site analgesia. Often performed using ultrasound or laparoscopic guidance, local anesthetic is injected between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles either before incision or at the conclusion of the procedure. This technique blocks somatic innervation of the lateral and anterior abdominal wall.10 TAP blocks have been shown to provide significant early and delayed postoperative pain control for patients undergoing laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy. Use of TAP block perioperatively was also associated with a reduction in opioid consumption in patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy, but not in patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy.11 For MIS, laparoscopic- and ultrasound-guided TAP blocks were found to be equally efficacious. Compared with port-site infiltration alone, laparoscopic TAP blocks provided better early postoperative pain control and lowered 24-hour opioid consumption.12

Multiple studies have evaluated the utility of local anesthetics at time of vaginal hysterectomy with either paracervical or uterosacral ligament infiltration. Although there is limited evidence suggesting uterosacral ligament infiltration reduces postoperative opioid requirement after vaginal hysterectomy, the paucity of high-quality randomized data prevents any definitive conclusions.13

After surgery

Multimodal analgesia is a staple in ERAS pathways and has demonstrated reduced reliance on opioids without compromising adequate control of acute postoperative pain.1 NSAIDs and acetaminophen are the mainstays of postoperative pain control. Administration of both is more effective than either one used alone,9 and around-the-clock administration is recommended over intermittent use. Although duration of use may vary depending on the surgery performed, most patients can be advised to use this combination around-the-clock for 3 to 5 days without long-term health consequences. Even in patients with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, a short course of NSAIDs has been proved to be safe. Although nephrotoxicity is not associated with short courses of NSAIDs, there are limited data to guide recommendations in patients with existing renal disease.14

Surgeons have an opportunity and even an obligation to prevent opioid misuse and overuse. Relying solely on opioids for postoperative pain can have detrimental effects on patient recovery due to adverse effects (eg, nausea, constipation, sedation) and can result in persistent opioid use disorder. It is estimated that 4.4% to 5% of opioid-naive patients report persistent opioid use following benign gynecologic surgery.15 Of individuals misusing opioids, 27% obtain the medication via physician prescription.16

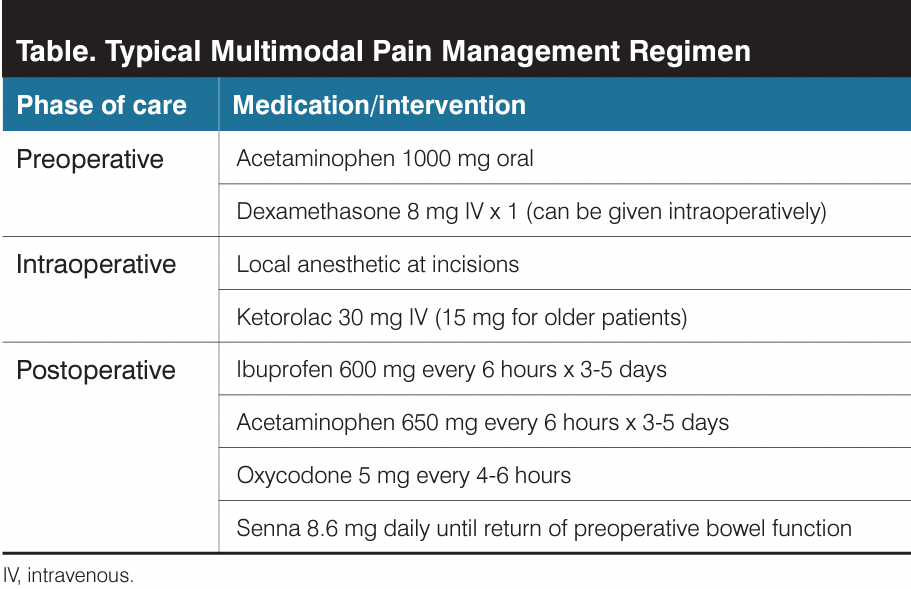

Although investigators from a recent study examining postoperative pain reported that 43% of patients, including those with chronic pelvic pain, required zero opioids following minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH),17 universal elimination of opioid prescription and use following gynecologic surgery is likely unrealistic. It can be challenging to know the ideal number of pills to prescribe, and without published guidelines, many surgeons overestimate patient need and dispense a customary quantity based on those needing the most.18 Systematic reviews of postoperative opioid use estimate that the average patient requires fewer than 9 oxycodone 5-mg pills following MIH and fewer than 15 following abdominal hysterectomy.15,19 Despite this, the average number of tablets prescribed far exceeds requirements, putting patients at risk for overuse and abuse.19,20 Prescription quantity upon discharge after inpatient or overnight stay should be tailored based on use while in hospital, otherwise prescribing 10 tablets or fewer of oxycodone 5 mg is considered sufficient and responsible. Additional efforts to reduce opioid misuse can be made by providing prescriptions at the time of discharge rather than in the preoperative setting (Table).

Providing patients with instructions regarding diet and functioning, although not directly related to pain, helps to promote adequate pain control. Bowel function is particularly important to address, as constipation is common following gynecologic surgery and can be distressing to patients. Senokot 8.6 mg daily is well tolerated and effective. Patients should be instructed to continue daily use until frequency of bowel movements returns to their preoperative state.

Recommendations for nonpharmacologic treatment of postoperative pain are lacking. Therapies that have been investigated include abdominal binders, ice packs, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, among many others. Almost all these interventions are patient directed and carry minimal to no risk. Patients interested in nonpharmacologic measures should be supported when the desired intervention poses no risk, regardless of whether there is likely benefit.

Special considerations

As described, multimodal pain management has reduced physician and patient reliance on opioid medications.21 Unfortunately, not all patients are candidates for one or more components of multimodal therapy. For patients reporting an allergy to opioids or contraindications to NSAID therapy, surgeons may be left in a pain management quandary.

The overwhelming majority of opioid allergies reported are not true immune-mediated IgE or T-cell reactions but represent adverse effects and non–immune mediated sensitivities, typically caused by endogenous histamine release from mast cells.22 Selecting the lowest-dose and/or highest potency opioid can help to reduce sensitivity. Reactions can be further reduced by concomitant administration of antihistamines and/or antiemetics. For patients with true anaphylactic reactions, alternative medications should be used.

The use of NSAID therapy following weight reduction surgery is typically discouraged secondary to a higher risk of peptic ulcer disease. For patients having undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, this risk is highest with NSAID use for more than 30 days. However, a review of 3 large national databases found no association with temporary use (< 30 days). Additionally, there was no association between NSAID exposure and the development of peptic ulcers after sleeve gastrectomy.23,24

The 2019 practice guidelines for perioperative care related to bariatric surgery, endorsed by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, acknowledges that limited NSAID use can be considered and that concomitant use of proton-pump inhibitors is vital to prevent ulceration.25 If NSAID therapy is decided upon, consideration should be given to the use of COX-2 NSAIDs as these are less likely to impair gastric mucous production, protecting the stomach from ulcer formation. Additionally, when prescribing medications for patients who have undergone prior weight loss surgery, enteric-coated pills should be avoided given that changes in gastric pH impair the disintegration of these medications. Liquid formulations or crushed tablets may have improved absorption.

Alternatives to standard multimodal therapy are unfortunately narrow. Gabapentin and pregabalin are antiepileptic drugs with a wide range of off-label use, including for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Early iterations of ERAS pathways included preoperative administration of gabapentin, but most modern pathways no longer include it given that concomitant use of opioids and gabapentin can increase dizziness and respiratory depression. For patients who cannot or do not want to take opioids, preoperative administration has been well studied and is associated with reduction in postoperative pain.9 Unfortunately, variable dosages between studies (gabapentin 900 mg-1200 mg, pregabalin 75 mg-300 mg) limits definitive dosing recommendations. Postoperative administration is less well researched but may be beneficial in patients with contraindications to postoperative opioids and/or NSAIDs.

As we consider the spectrum of therapies available, it is imperative to maintain a patient-centered approach in selection. Preoperative patient collaboration, communication of expectations and management, and multimodal pharmacologic therapies maximize postoperative pain control and patient experience.

References

1. Stone R, Carey E, Fader AN, et al. Enhanced recovery and surgical optimization protocol for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: an AAGL white paper. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(2):179-203. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.006

2. Dowdy SC, Kalogera E, Scott M. Optimizing preanesthesia care for the gynecologic patient. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(2):395-408. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003323

3. Latthe P, Panza J, Marquini GV, et al. AUGS-IUGA joint clinical consensus statement on enhanced recovery after urogynecologic surgery: developed by the Joint Writing Group of the International Urogynecological Association and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urogynecology (Phila). 2022;28(11):716-734. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000001252

4. Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(4):651-668. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2019-000356

5. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

6. ACOG Committee opinion no. 750 summary: perioperative pathways: enhanced recovery after surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(3):801-802. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002819

7. Atkins JR, Titch JF, Norcross WP, Thompson JA, Muckler VC. Preemptive oral acetaminophen for women undergoing total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Nurs Womens Health. 2019;23(2):105-113. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2019.01.003

8. Lombardi TM, Kahn BS, Tsai LJ, Waalen JM, Wachi N. Preemptive oral compared with intravenous acetaminophen for postoperative pain after robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(6):1293-1297. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003578

9. Wong M, Morris S, Wang K, Simpson K. Managing postoperative pain after minimally invasive gynecologic surgery in the era of the opioid epidemic. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(7):1165-1178. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.09.016

10. Mavarez AC, Ahmed AA. Transabdominal plane block. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024-.

11. Bacal V, Rana U, McIsaac DI, Chen I. Transversus abdominis plane block for post hysterectomy pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(1):40-52. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2018.04.020

12. Hamid HK, Emile SH, Saber AA, Ruiz-Tovar J, Minas V, Cataldo TE. Laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain management in minimally invasive surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(3):376-386. e15. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.05.020

13. Wang AS, Ouyang C, Carrillo JF, Feranec JB, Lamvu GM. Paracervical block or uterosacral ligament infiltration for benign minimally invasive hysterectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2021;76(6):353-366. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000901

14. Chang RW, Tompkins DM, Cohn SM. Are NSAIDs safe? assessing the risk-benefit profile of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in postoperative pain management. Am Surg. 2021;87(6):872-879. doi:10.1177/0003134820952834

15. Matteson KA, Schimpf MO, Jeppson PC, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Prescription opioid use for acute pain and persistent opioid use after gynecologic surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(4):681-696. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005104

16. Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Sources of prescription opioid pain relievers by frequency of past-year nonmedical use United States, 2008-2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):802-803. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12809

17. Cope AG, Wetzstein MM, Mara KC, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Warner NS, Burnett TL. Abdominal ice after laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(2):342-350.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.06.027

18. Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):709-714. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993

19. Johnson CM, Makai GEH. A systematic review of perioperative opioid management for minimally invasive hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(2):233-243. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.024

20. Shields JK, Kenyon L, Porter A, et al. Ice-POP: ice packs for postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30(6):455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.01.015

21. Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. Postoperative pain management after ambulatory surgery: role of multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;28(2):217-224. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2010.02.011

22. DeDea L. Prescribing opioids safely in patients with an opiate allergy. JAAPA. 2012;25(1):17. doi:10.1097/01720610-201201000-00003

23. Begian A, Samaan JS, Hawley L, Alicuben ET, Hernandez A, Samakar K. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(3):484-488. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2020.11.016

24. Skogar ML, Sundbom M. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of peptic ulcers after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18(7):888-893. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2022.03.019

25. Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(2):175-247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2019.10.025